Name: Toraja

Living Area: South Sulawesi, Indonesia

Population: 650.000

Language: Toraja

Comments:

The Toraja are an ethnic group indigenous to a mountainous region of South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Their population is approximately 650,000, of which 450,000 still live in the regency of Tana Toraja ("Land of Toraja"). Most of the population is Christian, and others are Muslim or have local animist beliefs known as aluk ("the way"). The Indonesian government has recognized this animist belief as Aluk To Dolo ("Way of the Ancestors").

The word toraja comes from the Bugis language's to riaja, meaning "people of the uplands". The Dutch colonial government named the people Toraja in 1909.

Before the 20th century, Torajans lived in autonomous villages, where they practised animism and were relatively untouched by the outside world. In the early 1900s, Dutch missionaries first worked to convert Torajan highlanders to Christianity. When the Tana Toraja regency was further opened to the outside world in the 1970s, it became an icon of tourism in Indonesia: it was exploited by tourism developers and studied by anthropologists. By the 1990s, when tourism peaked, Toraja society had changed significantly, from an agrarian model — in which social life and customs were outgrowths of the Aluk To Dolo—to a largely Christian society.

Toraja's indigenous belief system is polytheistic animism, called aluk, or "the way" (sometimes translated as "the law"). In the Toraja myth, the ancestors of Torajan people came down from heaven using stairs, which were then used by the Torajans as a communication medium with Puang Matua, the Creator. The cosmos, according to aluk, is divided into the upper world (heaven), the world of man (earth), and the underworld. At first, heaven and earth were married, then there was a darkness, a separation, and finally the light. Animals live in the underworld, which is represented by rectangular space enclosed by pillars, the earth is for mankind, and the heaven world is located above, covered with a saddle-shaped roof. Other Toraja gods include Pong Banggai di Rante (god of Earth), Indo' Ongon-Ongon (a goddess who can cause earthquakes), Pong Lalondong (god of death), and Indo' Belo Tumbang (goddess of medicine); there are many more.

The earthly authority, whose words and actions should be cleaved to both in life (agriculture) and death (funerals), is called to minaa (an aluk priest). Aluk is not just a belief system; it is a combination of law, religion, and habit. Aluk governs social life, agricultural practices, and ancestral rituals. The details of aluk may vary from one village to another. One common law is the requirement that death and life rituals be separated. Torajans believe that performing death rituals might ruin their corpses if combined with life rituals. The two rituals are equally important. During the time of the Dutch missionaries, Christian Torajans were prohibited from attending or performing life rituals, but were allowed to perform death rituals. Consequently, Toraja's death rituals are still practiced today, while life rituals have diminished.

Well-known by: Their funeral rites.

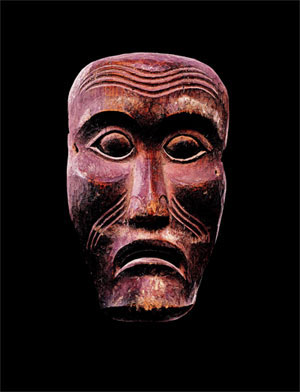

Torajans are renowned for their elaborate funeral rites, burial sites carved into rocky cliffs, massive peaked-roof traditional houses known as tongkonan, and colourful wood carvings. Toraja funeral rites are important social events, usually attended by hundreds of people and lasting for several days.

In Toraja society, the funeral ritual is the most elaborate and expensive event. The richer and more powerful the individual, the more expensive is the funeral. In the aluk religion, only nobles have the right to have an extensive death feast. The death feast of a nobleman is usually attended by thousands and lasts for several days. A ceremonial site, called rante, is usually prepared in a large, grassy field where shelters for audiences, rice barns, and other ceremonial funeral structures are specially made by the deceased family. Flute music, funeral chants, songs and poems, and crying and wailing are traditional Toraja expressions of grief with the exceptions of funerals for young children, and poor, low-status adults.

The ceremony is often held weeks, months, or years after the death so that the deceased's family can raise the significant funds needed to cover funeral expenses. Torajans traditionally believe that death is not a sudden, abrupt event, but a gradual process toward Puya (the land of souls, or afterlife). During the waiting period, the body of the deceased is wrapped in several layers of cloth and kept under the tongkonan. The soul of the deceased is thought to linger around the village until the funeral ceremony is completed, after which it begins its journey to Puya.

Another component of the ritual is the slaughter of water buffalo. The more powerful the person who died, the more buffalos are slaughtered at the death feast. Buffalo carcasses, including their heads, are usually lined up on a field waiting for their owner, who is in the "sleeping stage". Torajans believe that the deceased will need the buffalo to make the journey and that they will be quicker to arrive at Puya if they have many buffalo. Slaughtering tens of water buffalo and hundred of pigs using a machete is the climax of the elaborate death feast, with dancing and music and young boys who catch spurting blood in long bamboo tubes. Some of the slaughtered animals are given by guests as "gifts", which are carefully noted because they will be considered debts of the deceased's family.

There are three methods of burial: the coffin may be laid in a cave or in a carved stone grave, or hung on a cliff. It contains any possessions that the deceased will need in the afterlife. The wealthy are often buried in a stone grave carved out of a rocky cliff. The grave is usually expensive and takes a few months to complete. In some areas, a stone cave may be found that is large enough to accommodate a whole family. A wood-carved effigy, called tau tau, is usually placed in the cave looking out over the land. The coffin of a baby or child may be hung from ropes on a cliff face or from a tree. This hanging grave usually lasts for years, until the ropes rot and the coffin falls to the ground.

Some words in Toraja language:

hello: Apa kareba

thank you: Kurre sumange

how are you?: Kareba melo

© Text and images: Wikipedia